In the spring of 1781, during the American war for independence from Great Britain, redcoat troops arrived in upland Carolina and brought terror to Elizabeth Jackson and her sons. Elizabeth’s youngest son, Andrew, though barely fourteen years of age, hated their presence—and quickly learned just how costly the fight for liberty could be.

On April 9, Andy and his brother, Robert, two years older, joined a battle to defend the local meetinghouse against a band of Tories reinforced by British dragoons. The fight went badly for the Americans, but the brothers escaped and managed to reach their cousin’s home. Once there, however, their luck ran out: a Tory spy spotted their horses and informed the British of their whereabouts.

A British officer soon delivered a lesson in the cruelties of war. As the Jackson brothers stood helplessly at the point of British swords, the enemy set about destroying their aunt and uncle’s home. Determined to make an example of these rebels, the redcoats shattered dishes, ripped clothing to rags, and smashed furniture. Then, with the house in ruins, the commanding officer decided upon one more humiliation. He chose Andy Jackson as his target.

A British officer soon delivered a lesson in the cruelties of war. As the Jackson brothers stood helplessly at the point of British swords, the enemy set about destroying their aunt and uncle’s home. Determined to make an example of these rebels, the redcoats shattered dishes, ripped clothing to rags, and smashed furniture. Then, with the house in ruins, the commanding officer decided upon one more humiliation. He chose Andy Jackson as his target.

He ordered tall and gangly Andy Jackson to kneel before him and clean the mud from his boots. The boy refused.

“Sir, I am a prisoner of war, and claim to be treated as such.”

Enraged by the young American’s defiance, the British officer raised his sword and brought it down on Jackson’s head. Had Andy not raised his arm to deflect the blow, his skull might have been split open. As it was, the blade gashed his forehead and sliced his hand to the bone. Not satisfied at drawing blood from Andy, the soldier turned and slashed at his brother, tearing into his scalp, leaving him dazed and bleeding.

No one dressed their wounds. Instead, the Jackson brothers were marched forty miles, with neither food nor water, to join more than two hundred other rebellious colonists in a prison camp in Camden. There they were fed stale bread and exposed to smallpox.

Their mother, Elizabeth Jackson, had already lost too much. Her husband, Andrew Jackson Sr., had worked himself to death shortly before Andrew was born, leaving the pregnant Elizabeth with two, soon to be three, young sons in the rugged wilderness of upland South Carolina. She had raised the baby and his brothers as best she could and tried to protect them from the dangers of the war, but the boys had joined the fight for independence despite her pleas. Hugh, the oldest, had died at age sixteen of heat exhaustion after a battle the year before. Elizabeth was not about to lose her remaining sons now.

Traveling the long distance to their prison, she managed to persuade their jailers to include them in a prisoner exchange. But freedom didn’t mean safety. Robert had fallen dangerously ill, his wound infected, and the family of three had many miles to travel—on just two horses. Robert, delirious, rode one, and the exhausted Elizabeth the other.

Andrew walked. He made the journey barefoot, since the British had taken his shoes. Although all three made it home through driving rains, Robert died two days later. Elizabeth soon died from cholera.

Andrew Jackson would never forget the pain and humiliation of that summer. His father, mother, and brothers were dead. He himself bore the memory of British brutality, his forehead and hand forever marked by the British officer’s sword.

His mother left him with words to live by: “Make friends by being honest and keep them by being steadfast. Never tell a lie, nor take what is not your own, nor sue for slander—settle them cases yourself!”

Jackson would get his revenge 37 years later. On January 8, 1815, 5,300 British Troops—the same battle-hardened soldiers who had defeated Napoleon—under the leadership of General Edward Packenham directed a foolhardy frontal assault against Andrew Jackson’s 3,500 men who were dug in behind high mud walls near New Orleans. The result was more of a massacre than a battle. More than 2,000 British soldiers were killed, wounded, or missing in less than an hour. Only 13 Americans were killed and 58 wounded.

The British soon evacuated their remaining troops. America had won a second war for independence, and our young nation boldly stood at the precipice of national expansion and international power.

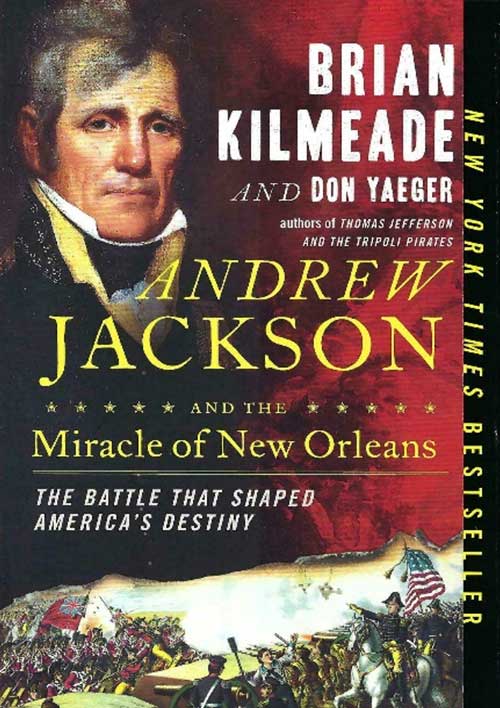

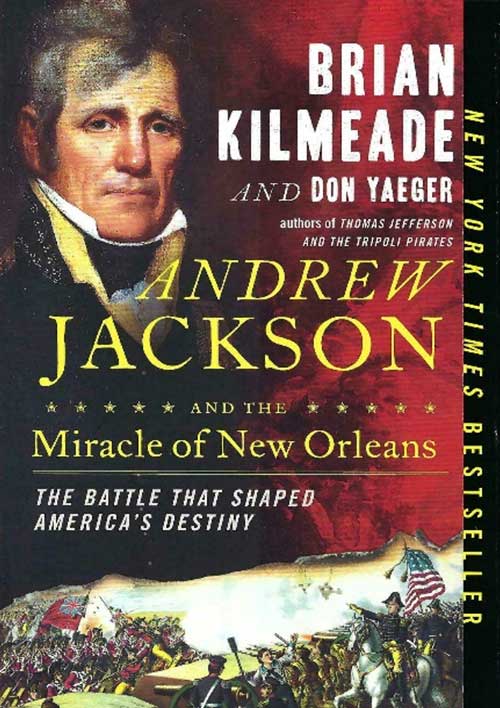

“Andrew Jackson and The Miracle of New Orleans: The Battle That Shaped America’s Destiny” by Brian Kilmeade and Don Yaeger is the story of a highly factionalized society coming together at a time of crisis and uniting their skills, valor, and spirit for the sake of preserving this nation. I can think of no message more timely or more important.

This book is available at the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore at 4440 13th Street in Ashland. For more information call 606-326-1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor

In the spring of 1781, during the American war for independence from Great Britain, redcoat troops arrived in upland Carolina and brought terror to Elizabeth Jackson and her sons. Elizabeth’s youngest son, Andrew, though barely fourteen years of age, hated their presence—and quickly learned just how costly the fight for liberty could be.

On April 9, Andy and his brother, Robert, two years older, joined a battle to defend the local meetinghouse against a band of Tories reinforced by British dragoons. The fight went badly for the Americans, but the brothers escaped and managed to reach their cousin’s home. Once there, however, their luck ran out: a Tory spy spotted their horses and informed the British of their whereabouts.

A British officer soon delivered a lesson in the cruelties of war. As the Jackson brothers stood helplessly at the point of British swords, the enemy set about destroying their aunt and uncle’s home. Determined to make an example of these rebels, the redcoats shattered dishes, ripped clothing to rags, and smashed furniture. Then, with the house in ruins, the commanding officer decided upon one more humiliation. He chose Andy Jackson as his target.

He ordered tall and gangly Andy Jackson to kneel before him and clean the mud from his boots. The boy refused.

“Sir, I am a prisoner of war, and claim to be treated as such.”

Enraged by the young American’s defiance, the British officer raised his sword and brought it down on Jackson’s head. Had Andy not raised his arm to deflect the blow, his skull might have been split open. As it was, the blade gashed his forehead and sliced his hand to the bone. Not satisfied at drawing blood from Andy, the soldier turned and slashed at his brother, tearing into his scalp, leaving him dazed and bleeding.

No one dressed their wounds. Instead, the Jackson brothers were marched forty miles, with neither food nor water, to join more than two hundred other rebellious colonists in a prison camp in Camden. There they were fed stale bread and exposed to smallpox.

Their mother, Elizabeth Jackson, had already lost too much. Her husband, Andrew Jackson Sr., had worked himself to death shortly before Andrew was born, leaving the pregnant Elizabeth with two, soon to be three, young sons in the rugged wilderness of upland South Carolina. She had raised the baby and his brothers as best she could and tried to protect them from the dangers of the war, but the boys had joined the fight for independence despite her pleas. Hugh, the oldest, had died at age sixteen of heat exhaustion after a battle the year before. Elizabeth was not about to lose her remaining sons now.

Traveling the long distance to their prison, she managed to persuade their jailers to include them in a prisoner exchange. But freedom didn’t mean safety. Robert had fallen dangerously ill, his wound infected, and the family of three had many miles to travel—on just two horses. Robert, delirious, rode one, and the exhausted Elizabeth the other.

Andrew walked. He made the journey barefoot, since the British had taken his shoes. Although all three made it home through driving rains, Robert died two days later. Elizabeth soon died from cholera.

Andrew Jackson would never forget the pain and humiliation of that summer. His father, mother, and brothers were dead. He himself bore the memory of British brutality, his forehead and hand forever marked by the British officer’s sword.

His mother left him with words to live by: “Make friends by being honest and keep them by being steadfast. Never tell a lie, nor take what is not your own, nor sue for slander—settle them cases yourself!”

Jackson would get his revenge 37 years later. On January 8, 1815, 5,300 British Troops—the same battle-hardened soldiers who had defeated Napoleon—under the leadership of General Edward Packenham directed a foolhardy frontal assault against Andrew Jackson’s 3,500 men who were dug in behind high mud walls near New Orleans. The result was more of a massacre than a battle. More than 2,000 British soldiers were killed, wounded, or missing in less than an hour. Only 13 Americans were killed and 58 wounded.

The British soon evacuated their remaining troops. America had won a second war for independence, and our young nation boldly stood at the precipice of national expansion and international power.

“Andrew Jackson and The Miracle of New Orleans: The Battle That Shaped America’s Destiny” by Brian Kilmeade and Don Yaeger is the story of a highly factionalized society coming together at a time of crisis and uniting their skills, valor, and spirit for the sake of preserving this nation. I can think of no message more timely or more important.

This book is available at the Jesse Stuart Foundation Bookstore at 4440 13th Street in Ashland. For more information call 606-326-1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor