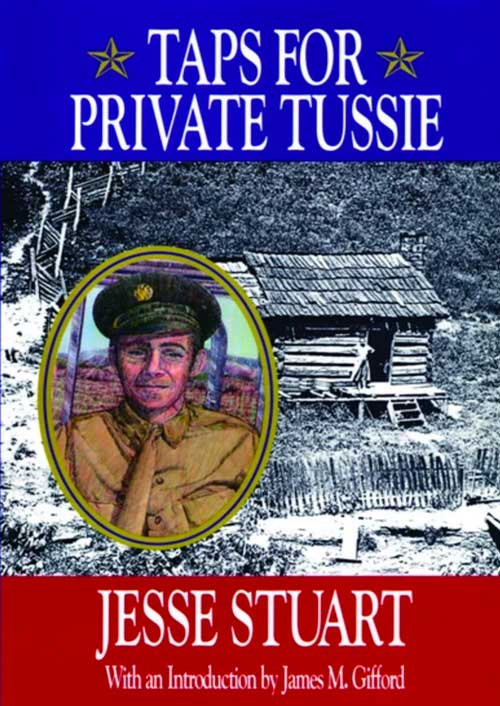

Taps For Private Tussie is Jesse Stuart’s best-known book. Published in 1943, Taps quickly captivated America’s reading public. It became an instant best seller, with over a million copies sold in the 1940s and 1950s. Taps became a Book of the Month Club selection in 1943, and also received the Thomas Jefferson Southern Award for the best Southern book of that year.

Taps For Private Tussie grew steadily in popularity. It was republished a number of times, and was translated into several foreign languages. The Ladies’ Home Journal published a condensed version in 1944. Within a year, Taps, like many other popular American books, had also been republished in the well-known smaller format of the Armed Services Editions.

Taps For Private Tussie grew steadily in popularity. It was republished a number of times, and was translated into several foreign languages. The Ladies’ Home Journal published a condensed version in 1944. Within a year, Taps, like many other popular American books, had also been republished in the well-known smaller format of the Armed Services Editions.

Taps continued to enjoy a wide audience after the war. MGM studios had purchased the movie rights for $50,000 and the Stuarts were very excited about a possible movie version. Unfortunately, MGM felt pressure from several quarters against going through with the film project. Army representatives, for instance, were particularly opposed to a film of the novel because they felt the basic story line, built around the mistaken identification of Private Kim Tussie’s body, could never have happened.

Although the book enjoyed continued nationwide popularity, some of Stuart’s Eastern Kentucky neighbors did not like it. They felt that Jesse’s portrayal of the Tussies was “pokin’ fun” at them.

Far from setting out to belittle his people, Stuart sought to be a positive spokesman for the people and institutions of his beloved Kentucky homeland. Nevertheless, it was his intent to make a political statement through Taps. The misadventures of the Tussies were meant to be a warning to all who shared “inherited indolence,” which was Stuart’s original title for the novel while it was still in manuscript form.

The story is told by Sid Tussie, a teenage boy living with an extended family that includes his Grandpa Press Tussie, the patriarch of a huge mountain clan, and Press’s wife, Arimithy. Both appear old to Sid, though in fact, they are only in their mid-fifties. The other family members include Aunt Vittie, the young widow of Kim Tussie, Press and Arimithy’s son who is thought to have been killed in World War II; Uncle Mott, Sid’s unmarried uncle, who is an alcoholic; and uncle George, Grandpa’s brother, a fiddle playing man of the world who has been married several times and has lived beyond the mountains for a number of years.

Sid, like many youngsters, accepts the strange world around him as normal, for he has no frame of reference that allows him to compare his life with the experiences of other young people. He does not know who his parents are, so he accepts Grandpa and Grandma as the authority figures in his life, and he loves them both.

Soon after Kim Tussie’s burial, the Tussies learn that Vittie will receive $10,000, Kim’s G.I. insurance. With that windfall, they rent one of the finest homes in the county and more than 40 relatives join their more comfortable life. The good life includes new clothes, new furniture, and “good grub,” although Grandpa continues his monthly trek to town to get his “relief grub,” too.

The joy of their rags-to-riches saga is short-lived. Hard times set in once more. The freeloaders go back to the hills, and Grandpa Tussie and his family make a long trek to a little cabin that Vittie has purchased with the last $300 of her “Kim money.”

The story concludes with Grandpa on his death bed. Mott has killed two distant relatives in a drunken rage and has fearfully returned, one step ahead of a local posse, to see Vittie. Before the sheriff and his men arrive, Mott quarrels with George, and George kills him in sad conclusion to this family feud. Readers already familiar with Taps will recall how Stuart resolves his plot. New readers will want to discover this for themselves.

In this world where you just cannot please everyone, Jesse Stuart had a very clear sense of both his mission and his audience. He chronicled, and implicitly praised, the everyday folks of Appalachia and America—the people whose work, whose passion, and whose shortcomings move us into the future, a day at a time. They were the people who bought millions of copies of Taps For Private Tussie, and they are the people who will continue to enjoy this unforgettable story.

I encourage you to read or re-read Taps For Private Tussie this summer. A new softcover edition is available at the Jesse Stuart Foundation. For more information, call (606) 326-1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor

Taps For Private Tussie is Jesse Stuart’s best-known book. Published in 1943, Taps quickly captivated America’s reading public. It became an instant best seller, with over a million copies sold in the 1940s and 1950s. Taps became a Book of the Month Club selection in 1943, and also received the Thomas Jefferson Southern Award for the best Southern book of that year.

Taps For Private Tussie grew steadily in popularity. It was republished a number of times, and was translated into several foreign languages. The Ladies’ Home Journal published a condensed version in 1944. Within a year, Taps, like many other popular American books, had also been republished in the well-known smaller format of the Armed Services Editions.

Taps continued to enjoy a wide audience after the war. MGM studios had purchased the movie rights for $50,000 and the Stuarts were very excited about a possible movie version. Unfortunately, MGM felt pressure from several quarters against going through with the film project. Army representatives, for instance, were particularly opposed to a film of the novel because they felt the basic story line, built around the mistaken identification of Private Kim Tussie’s body, could never have happened.

Although the book enjoyed continued nationwide popularity, some of Stuart’s Eastern Kentucky neighbors did not like it. They felt that Jesse’s portrayal of the Tussies was “pokin’ fun” at them.

Far from setting out to belittle his people, Stuart sought to be a positive spokesman for the people and institutions of his beloved Kentucky homeland. Nevertheless, it was his intent to make a political statement through Taps. The misadventures of the Tussies were meant to be a warning to all who shared “inherited indolence,” which was Stuart’s original title for the novel while it was still in manuscript form.

The story is told by Sid Tussie, a teenage boy living with an extended family that includes his Grandpa Press Tussie, the patriarch of a huge mountain clan, and Press’s wife, Arimithy. Both appear old to Sid, though in fact, they are only in their mid-fifties. The other family members include Aunt Vittie, the young widow of Kim Tussie, Press and Arimithy’s son who is thought to have been killed in World War II; Uncle Mott, Sid’s unmarried uncle, who is an alcoholic; and uncle George, Grandpa’s brother, a fiddle playing man of the world who has been married several times and has lived beyond the mountains for a number of years.

Sid, like many youngsters, accepts the strange world around him as normal, for he has no frame of reference that allows him to compare his life with the experiences of other young people. He does not know who his parents are, so he accepts Grandpa and Grandma as the authority figures in his life, and he loves them both.

Soon after Kim Tussie’s burial, the Tussies learn that Vittie will receive $10,000, Kim’s G.I. insurance. With that windfall, they rent one of the finest homes in the county and more than 40 relatives join their more comfortable life. The good life includes new clothes, new furniture, and “good grub,” although Grandpa continues his monthly trek to town to get his “relief grub,” too.

The joy of their rags-to-riches saga is short-lived. Hard times set in once more. The freeloaders go back to the hills, and Grandpa Tussie and his family make a long trek to a little cabin that Vittie has purchased with the last $300 of her “Kim money.”

The story concludes with Grandpa on his death bed. Mott has killed two distant relatives in a drunken rage and has fearfully returned, one step ahead of a local posse, to see Vittie. Before the sheriff and his men arrive, Mott quarrels with George, and George kills him in sad conclusion to this family feud. Readers already familiar with Taps will recall how Stuart resolves his plot. New readers will want to discover this for themselves.

In this world where you just cannot please everyone, Jesse Stuart had a very clear sense of both his mission and his audience. He chronicled, and implicitly praised, the everyday folks of Appalachia and America—the people whose work, whose passion, and whose shortcomings move us into the future, a day at a time. They were the people who bought millions of copies of Taps For Private Tussie, and they are the people who will continue to enjoy this unforgettable story.

I encourage you to read or re-read Taps For Private Tussie this summer. A new softcover edition is available at the Jesse Stuart Foundation. For more information, call (606) 326-1667 or email jsf@jsfbooks.com.

By James M. Gifford

JSF CEO & Senior Editor